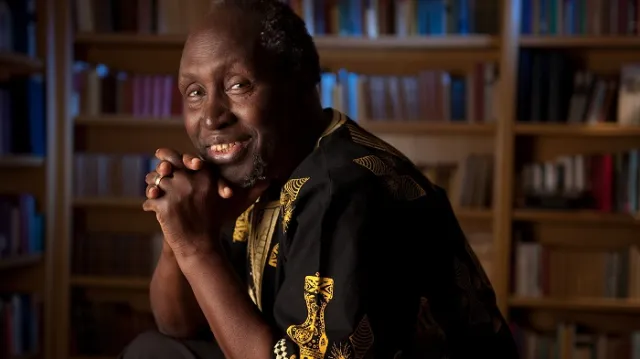

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is a huge figure in African writing, especially to Kenyan writers like me. He, along with Achebe and Soyinka, was part of a vibrant literary movement in the 1950s and 60s, as colonialism in Africa was ending. If Achebe captured the effect of colonization and Soyinka explored the clash of African tradition with Western ideas, Ngũgĩ was the bold activist. His writing was sharp and powerful, a tool against colonialism first and later against Kenya’s post-independence issues like corruption. If you are a Kenyan who attended primary and secondary school education in the 80’s and 90’s, then you had an opportunity to read his many works.

Since I am from a different tribe, not the Agikuyu, the most memorable book I read written by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was “The Trial of Dedan Kimathi,”. A play he co-wrote, with Micere Githae Mugo. What a masterpiece! I got hooked on the story of a Kenyan independence leader fighting a colonial court. Throughout high school, Ngũgĩ’s work was a big part of our studies in Kenya. In the late 60s, Ngũgĩ led a revolution at Nairobi University. It made the university switch from teaching English Literature to focusing on African stories, both spoken and written. Ten Ngũgĩ switched from writing in English to his native language, Gĩkũyũ, which I admired. His writing skills were a motivation to write and inspire readers worldwide. Without a doubt making him the champion of African literature.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Early Life

Ngũgĩ’s life mirrors the happenings in the 20th century. Born before World War II in Kenya under British rule, he grew up during the fight for independence. He studied in Uganda during a time of African political change, witnessing Uganda and then Kenya gaining independence. Yet, the post-independence period didn’t match the hopes he had seen. He was jailed for his writing by the Kenyan government. But continued his activism and writing in Kenya, London, and later in the US, teaching literature for 30 years. He’s renowned not just as a novelist but also as a key postcolonial thinker, notably for his 1986 essay collection challenging colonial languages’ dominance. Every year, there’s hope for him to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, yet it hasn’t happened, leading to disappointment.

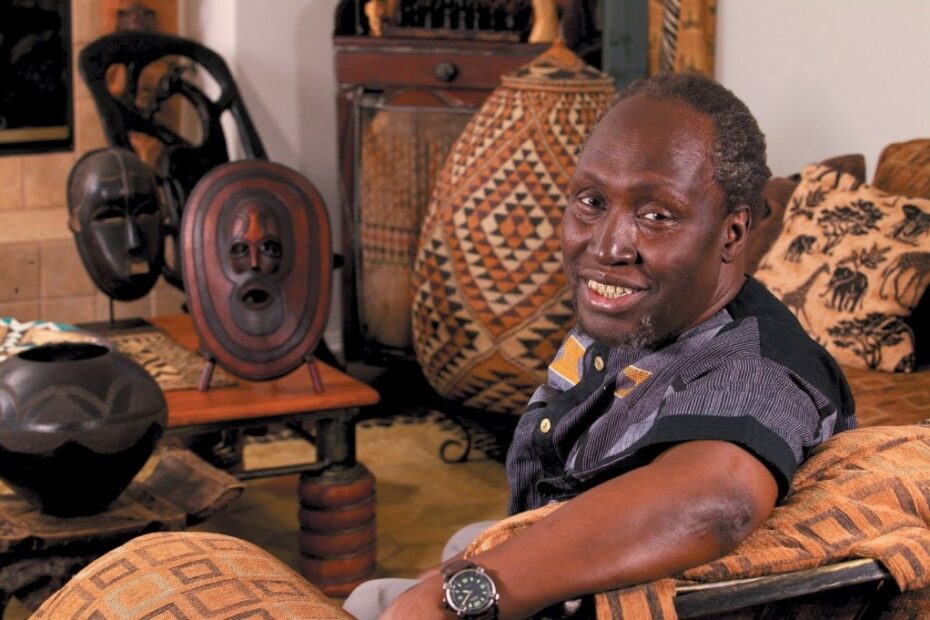

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is a multi-talented Kenyan writer, and professor at the University of California, Irvine. He penned memoirs like “Dreams in a Time of War: A Childhood Memoir” (2010) and “In the House of the Interpreter” (2012). His notable works also encompass novels such as “Weep Not, Child” (1964), “The River Between” (1965), “A Grain of Wheat” (1967), “Secret Lives” (1969), “Petals of Blood” (1977), and “Wizard of the Crow” (2009).

His Relationship with His Polygamous Father

In “Dreams,” Ngugi portrays his father, Thiong’o, as the head of a polygamous family, a reserved figure who didn’t speak much about his past, unlike our mothers who played a central role in our lives. Ngugi’s father did not influence his education. His mother worked hard to fund his primary schooling, sacrificing everything for her bright child’s education. The gap between Ngugi and his polygamous father was vast, forcing Ngugi to piece together his father’s life through others’ stories. Despite this, his father actively engaged in raising his children. Alongside occasional scolding with words he learned from his past British employers in Nairobi, he shared his meals and taught them etiquette.

So what changed his father into an aloof one?

Mild weather and incredibly fertile lands drew British settlers to the Kikuyu highlands, just as in South Africa and Zimbabwe. The British took most of the Kikuyu’s land, turning them into squatters on their ancestral grounds. This was significant because the Kikuyu, like many African communities, relied on the land for their livelihood. Displaced Kenyans had little choice but to work in uncertain jobs on White-owned farms and as servants for the growing White population in rural and urban areas. Land loss led to extreme commercialization that still affects Kenya’s economy and culture today.

Ngugi’s father managed to buy land in Kamirithu after saving money from working as a domestic servant for a White family. But a more privileged Kenyan, Lord Reverend Stanley Kahahu, claimed the land using the colonial legal system. Undeterred, Ngugi’s father persisted, becoming a successful goat and cattle farmer. However, a mysterious epidemic wiped out his entire herd, leaving him bitter and changed. This experience diminished the once-confident patriarch who, as Ngugi mentioned in ‘Dreams’, used to let each wife manage her household but now tried to control the entire homestead. His abusive outbursts culminated in kicking out Ngugi’s mother and her children.

British Colonial Impact on Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Teenagerhood

The British fought against a Kikuyu uprising in the 1950s, making Ngugi’s teenage years even tougher. The Kikuyu, stripped of their land, tried to fight back in a guerrilla war called the Mau Mau. Ngugi’s brother, back from fighting in World War II, joined the Mau Mau. This exposed their family to violent attacks by the British. Ngugi’s memoirs revealed truths about the Mau Mau uprising that historians didn’t capture – how serious the rebellion was and how brutal the British were.

It showed what life was like for an average Kikuyu during those times. Through vivid storytelling, someone younger from Kenya like me could understand the intensity of that period in British Africa. Ngugi’s memoirs shed light on crucial parts of recent African history, beyond just the involvement of fathers, like the impact of land loss and the British response to the Mau Mau.

Exploring African Women’s Experiences in Ngugi’s Writing Amid British Colonization

African gender studies have shown how colonial rule affected African women’s lives. Ngugi’s story vividly depicts the hardships women faced under the colonial “customary law.” When his father faced difficulties, he began taking his wives’ earnings from the land and his daughters’ wages from farms and factories. Ngugi’s mother, fleeing her abusive husband, sought refuge with her wealthy father. However, traditional practices hindered her access to land rights, delaying her independence. This made it tough for her to care for Ngugi and his siblings after their father kicked them out.

Colonialism also symbolically marginalized African women. Among the precolonial Kikuyu, it was normal for people to use their mother’s name as a surname—a practice that ended during colonial times. Ngugi used to be Ngugi wa Wanjiku until he went to school, where the teacher changed his surname to Thiong’o, erasing his mother’s name. This shift in surname, unnoticed by historians, highlights how literature captures real-life nuances. Ngugi’s “Dreams” not only reveals Kikuyu’s precolonial naming tradition but also touches on the violence in late nineteenth-century Africa. Ngugi’s grandfather was originally a Masai child who became part of the Kikuyu community, showing a blend of cultures.

The Two Memoirs of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

In his memoir, Ngugi explains how his father shifted from being a domestic servant for a Nairobi family to a smallholding farmer. This reveals a lot about the chances for social movement in colonial Africa.

Even though Thiong’o, Ngugi’s father, faced challenges, Ngugi, who once saw education as an impossible dream, later gained global recognition in the literary realm. The memoirs of this famous writer reveal the risky life and the huge chances for climbing the social ladder in British colonial Africa.

Ngugi’s memoirs offer more than just a captivating personal tale or insights into the life of a famous figure. They provide a view into the intricate nature of African life and the rapid changes that defined twentieth-century Africa. Regarding the British anti-Mau Mau efforts in the 1950s, it’s noteworthy how Ngugi’s generation of African intellectuals, who faced colonial repression during the independence era, displayed remarkable positivity and forgiveness.

James and Ngũgĩ

Ngũgĩ’s career neatly splits into two phases. First, as James Ngugi (or JT Ngugi) at Makerere University in the late 1950s to the late ’60s, he wrote in English. His early works subtly criticized colonialism, portraying protagonists who saw education as a weapon against colonizers, blending local traditions with Western ideals, but ultimately faced failure.

Then came the transformation in the ’70s. Ngũgĩ shed his English name, rejecting the language for his literary pursuits. Influenced by Marx and Frantz Fanon, his later works directly confronted postcolonial life, tackling state, class, and education. “Petals of Blood,” published in 1977, marked his shift to writing as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and his departure from writing in English. Here, education was no longer liberated; instead, it was the educated elite who betrayed the people. This marked the start of what critic Nikil Saval described as “the furious mid-phase of Ngũgĩ,” denouncing Kenya’s bourgeoisie and their attempts to replicate the colonial world they once rejected.

James Ngugi was deeply absorbed in the craft of writing. He meticulously pondered over style, the placement of words, and sentences. In most interviews, he mentioned that James was inspired by his literary hero Joseph Conrad. He once expressed how Conrad’s well-crafted sentences from “Nostromo” or the opening bars of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony could help end his writer’s block.

Shift to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

However, for Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, political messaging took precedence over style. His work strongly criticized Western religion, education, language, and Kenya’s post-independence leadership.

Ngũgĩ’s evolution can be seen in the revisions of “A Grain of Wheat.” In an important scene depicting LFA fighters attacking and raping a British settler, this incident was only present in the first edition. In later revisions, Ngũgĩ removed the rape scene, portraying the fighters differently. When asked about this change, Ngũgĩ explained,

“There wasn’t a recorded instance of such a rape in Kenya’s history. I didn’t want my novel to misrepresent Kenya’s struggle.”

The Language shift from English to Gĩkũyũ

In one interview with a Kenyan writer Carey Baraka, in his home in California, Ngugi expressed

“I don’t see the world through ethnicity or race,”. Race can come into it but as a consequence of class.” He cited this by giving the example of the US Supreme Court Justice, Clarence. He pondered

“He’s as black as me, but every law he passes is against black people – but not the black middle class. The black working class.”

During the 1970s, he was imprisoned by Kenya’s post-colonial government for co-authoring a play in an African language that echoed critical themes he had previously discussed in English. The play, “Ngaahika Ndeenda” (I Will Marry When I Want), was stopped by the government. This led to Ngũgĩ, a Literature Professor, to be placed in a maximum-security prison. Upon release, fearing threats, he fled Kenya and lived in exile for two decades.

Ngũgĩ highlights that European colonialism also affected places like Ireland. He mentions how, by the late 16th century, the English hadn’t fully conquered Ireland. He suggests two strategies used: erasing the native naming system and suppressing the Irish language. The aim was to make the Irish people lose their identity. Hence confirming his reason for shifting to the Gĩkũyũ language.

“Decolonizing the Mind” by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

‘Decolonizing the mind’ advocates for linguistic decolonization by reclaiming native languages imposed by colonial powers. Ngugi acknowledged the differences in colonial impacts between Kenya and Ireland. He discussed the need to explore the linguistic effects of 20th-century colonialism in Kenya from an Irish viewpoint. There might be valuable lessons here. He offers insights into how externally enforced language-shift policies and attitudes toward native languages operate in post-colonial societies.

The book “Decolonising the Mind” proposes that the linguistic conflict in Africa began with the Berlin Conference. During this event, European capitalist powers divided the diverse African continent, comprising numerous peoples, languages, and cultures, into different colonies. Culturally, this led to the imposition of European languages. The purpose was to shape the colonies’ self-identification primarily through this language. Similar to how some define Ireland today solely as ‘an English-speaking country.

Language and Colonization

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o argues that in every instance of colonization, language plays a pivotal role. It suppresses the native language while promoting the colonial one. He illustrates this by citing instances such as the Caribbean plantations where speaking African languages was prohibited, leading to severe consequences. Similar language attitudes, he notes, are historically evident in diverse locations like Canada, South America, Japan, New Zealand, and Australia.

Initially, colonial powers established control through violence, followed by efforts to suppress resistance via cultural assimilation and enforced education. While violence may harm the body, ‘Language became the tool for spiritual domination.’

In 1952, during a state of emergency in Kenya, all schools came under colonial control, imposing English as the primary language of education.

Punishment for Speaking Local Dialect

In Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s school, speaking the local language resulted in harsh punishment like caning. Or wearing a metal sign bearing humiliating phrases like ‘I AM STUPID’ or ‘I AM A DONKEY’. These signs aimed to degrade the native language speakers, strategically demeaning their language while glorifying the colonial tongue.

Another tactic involved a button given to the first child caught speaking their native language, who then passed it on to others caught doing the same. At the end of the day, the last person holding the button had to identify the child who gave it to them. This turned children into informers and taught them the value of betraying their community.

While native languages were belittled, English was celebrated. Students excelling in spoken or written English received praise, applause, and prizes.

Subjects like history, geography, and music perpetuated a Euro-centric view. The colonial language conveyed a culture designed to fracture the child’s identity, community, and sense of belonging.

In schools, emphasis was on established English-language books, while oral literature in Kenyan languages disappeared. This shifted the focus to an Anglo-centric worldview detached from the native identity.

Accessing Secondary School depended on English exam performance in six subjects. Failure in English meant overall failure, regardless of other results.

As an academic, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o engaged in debates about post-colonial Kenya’s education system. The discussion revolved around prioritizing colonial language and culture versus teaching about one’s own culture and society first, expanding to broader worldviews. This echoes Pádraig Pearse’s emphasis on an education system serving the native language, culture, identity, and society.

The Value and Identity of Native Language

Wa Thiong’o underscores language as a key element of culture, shaping our worldview and identity. Imposing a foreign language disrupts and distorts the colonial subject’s sense of self. Colonialism misleadingly portrays native languages as divisive while positioning the colonial language as a unifying force.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o views language as a vessel for a community’s history. The colonial language embodies the culture, values, and economic interests of its nation. Language influences how we perceive ourselves, both individually and collectively, preserving the worldview of its speakers. It serves as a conduit for the ‘values that shape our self-perception and our role in the world.’

Why Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has Never won the Nobel Literature Prize

The reasons why Ngũgĩ hasn’t received the Nobel Prize remain a mystery known only to the Swedish Academy. Speculations suggest his radical nature, unlike previous Black African winners, could play a role. His work, like “Devil On the Cross,” faced rejection by US publishers for its strong political convictions and specialized audience appeal. The book focused on contemporary African literature or Marxist thought.

Critics suggest that Ngũgĩ’s political strong will at times overshadowed his artistry. Some, like Nigerian critic Adewale Maja-Pearce, argue that his shift to writing in Gĩkũyũ cost him the refined artistry evident in his English-language novels. Now replaced by what is considered the crudest politics.

While praised for his anti-colonial literature, some critics, like Ugandan novelist Jennifer Makumbi, feel Ngũgĩ’s plays fell short, resembling more propaganda than profound storytelling.

When approached about the Nobel, Ngũgĩ often downplays its significance, suggesting the committee’s lack of interest in writers using African languages. However, his son, Mũkoma wa Ngũgĩ, commented after the 2022 award that the Nobel Literature Prize might as well be termed the Nobel Prize for European Literature with occasional nods to others.

Bottomline

Looking back, my disregard for literature was naive; it’s deeply connected to real life. I used to brush off teachers saying this, but thanks to Ngugi, and other writers, I see things differently now. The irony. Ngũgĩ was an exemplary student at Alliance. His debut published piece, featured in the school magazine in 1957, was penned by JT Ngugi, Form 3A. He praised British education and lauded Christianity as a significant force that civilized the Gĩkũyũ by steering them away from witchcraft. Ironically, while at school assemblies, he sang God Save the Queen, while his brother fought in the forests against the terror inflicted by her soldiers. So why the shift? If he continued with the refined English artistry, maybe the Nobel Literature Prize would be home by now. The contrary opinions remain debatable, and the jury is out there.