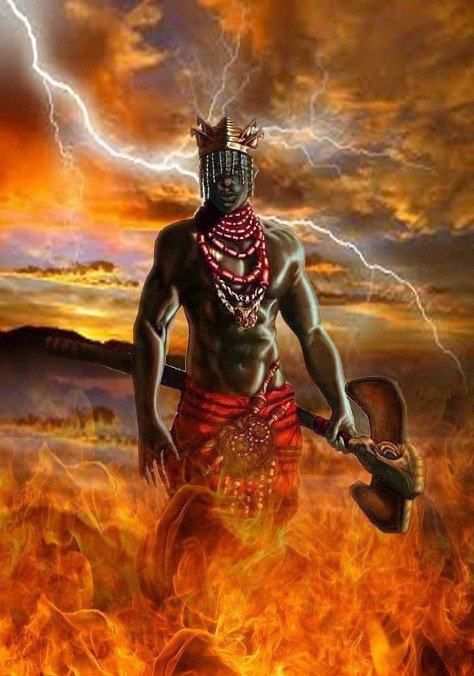

In Yoruba mythology, Sango Olukoso also known as Jakuta is perhaps the most popular Orisha. He is god of thunder and lightning and as well one of the most worshipped gods all over the world. His widespread worship spans across the globe, making him a prominent deity. Sango held a significant position in Yoruba history as the third king of the Oyo Kingdom, succeeding Ajaka, the son of Oranmiyan. His regal lineage has a symbolic double-headed axe, embodying the principles of swift and balanced justice. So, why was Sango a Yoruba god of thunder?

According to mythology, Sango and fourteen others were born by the goddess Yemaja after her son, Orungan, attempted a second rape on her. In alternative tales, Sango is the offspring of Aganju and Obatala. The narrative unfolds as Obatala, the king of the white cloth, faces resistance from Aganju, the ferryman and god of fire. This led to a transformative event where Obatala exchanged genders to secure passage. This theme led to conspiracy theories about historical homosexuality. The tension between reason, represented by Obatala, and the fiery nature of Aganju laid the groundwork for Sango’s distinctive character.

During Alaafin Ajaka’s reign, the Oyo Empire faced constant threats from Olowu, Ajaka’s cousin and ruler of the Owu Kingdom. To rescue Alaafin Ajaka from capture, the Oyomesi sought help from Sango, who successfully intervened. However, Sango ascended to the throne, sending Alaafin Ajaka into exile.

The Rule of Sango Olukoso Yoruba god of thunder

In the course of his rule, Sango had two formidable generals, Timi Agbale Olofa-ina and Gbonka. Advised by Oya, Sango opted to eliminate them, sending them to govern border towns. Gbonka, however, posed a persistent threat, leading to a series of conflicts. In a bid to neutralize both generals, Sango ordered Gbonka’s capture, resulting in a re-match between Gbonka and Timi. Gbonka emerged victorious, prompting Sango to order his incineration. He feared Gbonka would discover his true intentions. Miraculously, Gbonka reappeared after three days, issuing an ultimatum for Sango to relinquish the throne.

Enraged, Sango sought his Edun-Ara from Oya, only to find it stained with menstrual blood. In a fit of anger, he left the palace for a high rock, unleashing a thunderbolt that engulfed the palace in flames. Heartbroken, he departed the town, trailed by the Baba-Mogba, his royal cult, pleading for him to stay. Despite their efforts, Sango vanished, and some Baba-Mogba later discovered the truth that Gbonka had attacked him.

The Death of Sango Yoruba god of thunder

Contrary to rumors that Sango hanged himself, only a few Baba-Mogba knew the real story. Sango confronted Gbonka, disappearing momentarily before reappearing in the sky with fiery wrath to revenge against his adversary. The town spreading false rumors also faced Sango’s divine retribution. The phrase “OBAKOSO” or “OLUKOSO,” meaning the king did not hang, originated from the Baba-Mogba who knew the truth. Another interpretation links the name to the place where Sango triumphed over Gbonka, asserting his supreme reign.

Since then, Sango represents a deity during worship associated with thunder and fire, embodying the fiery temperament he exhibited during his time on earth and that of his devotees, known as “Mọgbà or Maagbà,” signifying “I will accept.” Similar to numerous Yoruba gods, Shango remain revered in various Caribbean traditional religions, including Santeria, Candomble, and other related practices.

Sango Worshippers

Sango is always seen wearing red, and his followers also wear bright red, making them easily recognizable in town. He is known for carrying an “axe-looking weapon” called an “òṣé,” which is like a staff used to show strength and control thunder and lightning (similar to Thor’s Mjolnir). Sango worshippers often have the word “Sango” or “Àrá,” meaning thunder, in their names. For example, my great-grandfather, from a family of Sango worshippers, was named “Àrágberí,” meaning “thunder conquers.”