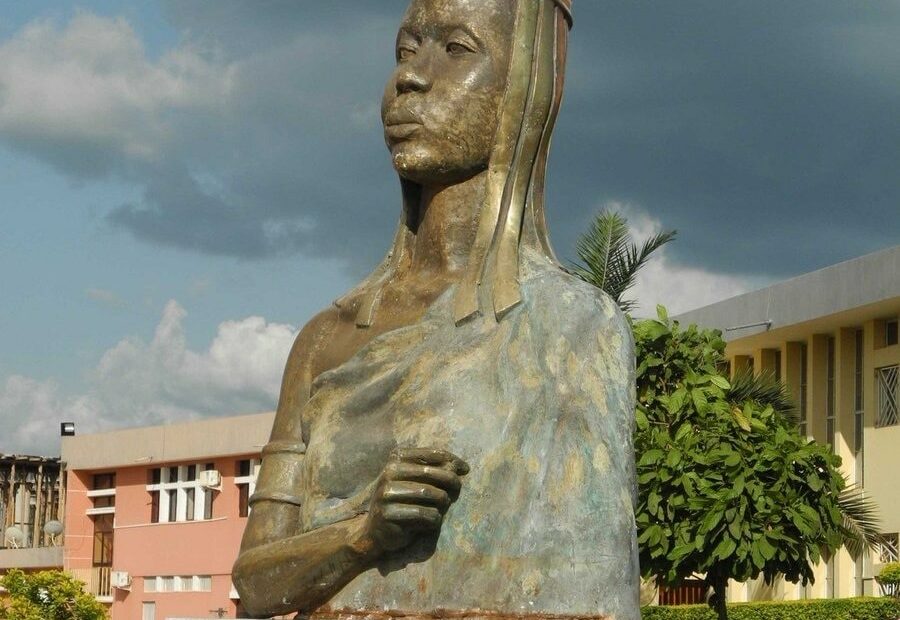

Centuries before and during European colonization in Africa, the continent flourished with ancient kingdoms and empires. Among their leaders were women. Among them, were warriors who bravely led armies against European invaders, defending their people from conquest and enslavement. Despite their remarkable feats in combat, the narratives of these Black women often remain overshadowed and underexplored. Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita was an incredibly charismatic woman. In the late 1700s, she led a messianic movement in honor of Saint Anthony. She advocated for Kongolese peasants, both men and women. Kimpa Vita, also called Chimpa Vita, was born around 1684 in the kingdom of Kongo. After Catholic missionaries baptized her as Dona Beatrice, her life became a symbol of resistance against the European invasion and takeover of Africa in the 17th century.

A Flourishing Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo, spanning parts of modern-day Central and Southern Africa, encompassed regions within the present-day Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, Gabon, and Angola. Its rich history began long before the arrival of the Portuguese in 1452. Before the Portuguese encounters, Kongo thrived as a highly developed society. Abundant resources like gold, copper, and ivory contributed to its wealth. The kingdom boasted advanced political structures and well-established educational and spiritual systems. Kongo had an organized governance segmented into provinces like Soyo, Mpemba, Mbamba, Loango, Kakongo, and Ngoyo, each led by governors appointed by the elected king “Ne Kongo”.

The Portuguese Invasion

Kongo’s main city Mbanza Kongo, is found in today’s Angola. When the Portuguese arrived there, they saw a strong and well-organized kingdom. They compared Mbanza Kongo to a fancy city in Portugal called Évora. But this made European countries like Portugal, the Netherlands, Germany, and Britain want more.

These countries used things like religion, wars, deals, and trade to speed up the kingdom’s end. Soon, Mbanza Kongo turned into a port. Portuguese traders took ivory, copper, and sadly, people from there. They needed these people for work on sugarcane farms in São Tomé. At first, they bought people, but later they started taking them forcefully.

King Nzinga Mvemba, also called Alfonso I, ruled from about 1506 to 1543. He wrote to the King of Portugal, telling him about how badly his people were treated. But even when he tried to stop the slave trade, it kept happening. This weakened the king’s power and ruined Kongo’s way of life.

A Divided Kingdom

During the 1600s, the Portuguese got more forceful in trying to take over the kingdom and its riches. In October 1665, a fight broke out between Ne Nlaza or King Antonio I (also known as Nvita a Nkanga in other historical writings) and the Portuguese over a gold mine. Ne Nlaza lost the battle of Mbwila and was killed by the Portuguese.

His death caused a big problem: the royal family and most of the rulers vanished, leaving a gap in leadership. The kingdom, which used to be one united place, got split into many parts. There were six provinces in the 1500s, but by the 1700s, there were twenty-two. This shattered the unity Kongo once had. Instead of order, there was chaos, and the Bakongo people didn’t trust or want Europeans around anymore.

Explaining the resentment of Bakongo’s towards the Portuguese, during the reign, Mbemba wrote saying

“The Kongo people strongly dislike Europeans because they don’t practice what they preach in religion. They say all Catholic people are like family, united. But the actions of those who claim to follow the Bible don’t match up. They wonder about this God of the Whites, supposed to be universal, but with saints who look just like them. These so-called servants of God don’t honor Kongo’s ways, customs, or traditions. Still, not everyone doubts the Christian faith!”

The Birth of Kimpa Vita

Kimpa Vita/Chimpa Vita was born during a time of political, social, and religious change. The exact date of Kimpa’s birth isn’t known. But it’s believed to be in the late 17th century, a period when the once-mighty kingdom of Kongo was declining. Some think her name might have been Europeanized by missionaries who weren’t fluent in the Bakongo language, a common practice among colonizers who often changed African names to European ones.

Martial Sinda, drawing on Bakongo beliefs about names, explained that a Mukongo name had deep meaning tied to specific events or symbols. According to him, “Kimpa” could mean fable, legend, mystery, or someone with a challenging character. While “Vita” might suggest an ambush or trap in times of war. This could imply difficult circumstances during Kimpa’s birth or challenges faced by her family.

Another name used for her, Chimpa Nsimba, refers to the name given to twins in the Kongo kingdom. Catholic priests claimed she was a Nganga Marinda, a mediator or messenger of a spiritual group called Marinda, known as Bansimba among the Bakongo. They are linked to the priestesses of the twins’ society. In essence, Kimpa/Chimpa Vita’s name reflects the rich philosophy, customs, culture, and traditions of the Bakongo people.

Kimpa Vita’s Liberation of Kongo People

Kimpa’s efforts to free and revive the kingdom were diverse, involving spirituality, politics, and morality. Historical records show she didn’t aim to become Kongo’s ruler but instead forged a new religion blending Catholicism with Kongo beliefs. A vision of Saint Anthony inspired her to lead her people, creating a religion that aligned with Bakongo culture and values. Her goal was to awaken her people to the challenges they faced, emphasizing their power for deliverance, contrary to a foreign God.

Seen by the Bakongo as a response to their prayers, Kimpa transformed Catholic hymns, instilling pride in the Kongo kingdom’s restoration. Designating Bakongo men as “angels” to spread her new religion, she urged unity to prevent disaster, echoing the teachings of earlier prophetesses.

Known for miracles and healing, she gained worship from kingdom leaders. Her teachings focused on self-prayer and kingdom salvation, upholding Kongo moral virtues while rejecting certain Catholic practices like baptism, confession, and marriage sanctity, viewing polygamy as part of Bakongo culture.

Despite not aspiring to rule, she acted as a peacekeeper among contenders for the throne, convincing them to gather in Mbanza Kongo for unity’s sake. Her presence there increased the city’s population during a time of decline due to wars and the slave trade, advancing her goal of restoration.

Remarks from Bernardo da Gallo (Catholic Priest), Kimpa Vita’s Greatest Enemy

“It happened that San Salvador (Mbanza Kongo) filled up fast. Some came to honor the supposed saint, others to witness a revived homeland, and some sought healing miracles. Some were drawn by ambitions of ruling and claiming the spot first. Consequently, the false saint was hailed as the savior, ruler, and master of Congo. She seemed acclaimed, respected, and worshipped by all. Contrarily, I was seen as weak, cowardly, and morally corrupt for not having the courage to go to San Salvador (Mbanza Kongo) or rally the people to restore the kingdom as their supposed saint had done.”

Bernardo da Gallo, Catholic Priest

This part reveals Kimpa Vita’s leadership and her ability to bring the Bakongo together. Sadly, her efforts were cut short by her arrest and sentence to death by burning. Labeled a fraud and witch by Catholic missionaries, they were complicit in her demise.

The Death of Kimpa Vita

The disarray and collapse of the kingdom became advantageous to Catholic missionaries, leading them to view Kimpa as an adversary. Consequently, they considered her a threat to their interests and collaborated with the king (Nusama a Mvemba/Pedro IV) to apprehend and convict her. Bernardo da Gallo’s interrogation of her sheds light on the motivations driving the priests’ actions.

While condemning her he said:

Bernardo Da Gallo, Catholic priest

“I inquired about her identity. She claimed to be Saint Anthony from heaven. I asked about the news from above, wondering if there were Congolese Black people in heaven and if they retained their Black color. She responded that in heaven, there were Congolese individuals, both young ones baptized and grown-ups, who followed God’s teachings. However, she mentioned that in heaven, there’s no distinction of color—neither black nor white exists there.”

Condemnation based on Religious Disagreement

Bernardo da Gallo, the Catholic missionary, harbored a strong dislike for Kimpa and sought her condemnation, ostensibly driven by religious differences. However, Kimpa’s use of religion to awaken her people, end colonization, and revive the kingdom contradicted these intentions. Her death was seen as crucial to halt this movement, and King Nusama a Mvemba/Pedro IV’s perception of her as a threat to the throne aided Bernardo da Gallo in ensuring her sentencing to death by fire.

Her execution by burning on July 2, 1706, was not a part of the Kongo judicial system. In Kongo’s criminal law, severe penalties for grave offenses involved slavery, ostracism, or fatal execution by burying culprits alive. Death by fire was not part of these traditions. Some scholars suggest that Kimpa’s sentence might have resulted from an agreement between the king and the missionaries, possibly in exchange for military support. This act also showcased the growing control that Europeans exerted over the kingdom.

Bottomline

After the execution, the executor, a Catholic priest Bernardo da Gallo mocked the people of Kongo by saying

“I decided their fate and corresponded to ensure they wouldn’t suffer from hunger. Dom Manuel convened with the royal council, excluding any influence from me, as though I wasn’t involved at all.”

The narrative of Kimpa Vita highlights the African continent’s resistance against European invaders or colonizers. It emphasizes the significant role women played in resisting exploitation and colonization in Africa.